Debt of Gratitude: Lin-Manuel Miranda and the Politics of US Latinx Twitter

Résumé (en traduction)

Cet article, qui entreprend d’analyser l’invocation par Lin-Manuel Miranda de « pour vous » sur Twitter en la comparant à celles de douze autres écrivains latinx, a deux objectifs : identifier les tendances principales des stratégies discursives utilisées plus largement sur le Tweeter latinx et plaider en faveur du besoin urgent de documenter de manière éthique et d’archiver la production contemporaine du Tweeter latinx. L’auteur s’achemine vers la création d’une archive académique publique du Tweeter latinx en publiant en ligne un corpus limité des tweets « pour vous» de Miranda ainsi que des visualisations comparatives de la manière dont l’emploi de «pour vous» par Miranda dans ses tweets entre à la fois en parallèle et en contraste avec celui d’autres auteurs latinx. Outre l’exemple qu’il donne du processus imparfait de la construction d’une archive en vue d’encourager d’autres universitaires à partager de manière attentionnée leurs propres processus d’archivage Twitter, cet article analyse les stratégies employées par certains écrivains latinx des Etats-Unis pour naviguer sur Twitter et comment ces stratégies peuvent témoigner de la manière dont ces écrivains envisagent les rapports entre les institutions, les publics et l’esthétique. L’article souligne tout particulièrement les travaux digitaux de la dramaturge cubano-américaine Marissa Chibas, du poète portoricain Rich Villar et de l’écrivain portoricain Charlie Vázquez sur Twitter en contrepoint à l’esthétique de Miranda. Il reste beaucoup de travail à faire pour comprendre comment Twitter agit comme véhicule pour Miranda et les nombreux écrivains latinx qui communiquent avec des publics et entre eux comme moyen de transformer l’émotion en action, en profit, ou en tout autre chose.

Introduction

On 17 July 2018, Nuyorican playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda tweeted about his forthcoming book from Random House, Gmorning, Gnight! Little Pep Talks for Me and You.1 Framing it as a cultural product that was created with a specific audience in mind, Miranda explained, “At YOUR request, we made a book.”2

Miranda’s use of “you” on Twitter more generally reflects a strategic invocation of his audience. The direct address cultivates intimacy with an assumed universal subject, in the sense that the follower is not identified in terms of gender, race, class, or sexuality. Adopting a grateful caretaker persona, Miranda provides his followers with a daily routine of feeling appreciated and valued, while also offering advice about how to adopt a more hopeful and productive outlook on life. Miranda’s performance of his public persona on social media is of particular importance because he is one of the US Latinx writers with the largest followings on Twitter, having broken the two-million-follower mark in December 2017. A constant stream of content, whether in the form of a greeting routine or music playlists, sustains a dynamic of intimacy on Miranda’s Twitter feed. In turn, his Twitter aesthetic relies on the creation of an emotional debt economy: providing an excess of expressions of appreciation and gratitude for his followers so that they feel indebted to him. Appeals to emotion enable Miranda to mobilize his followers and their purchasing power. Miranda encourages his followers to invest their time and money in his career as an artist and in various humanitarian causes. Often blurring the line between the personal, the profitable, and the political, Miranda’s Twitter production is productively contextualized by reviewing his prior marketing strategies for the 2008 Broadway musical In the Heights and his family background in political lobbying.3

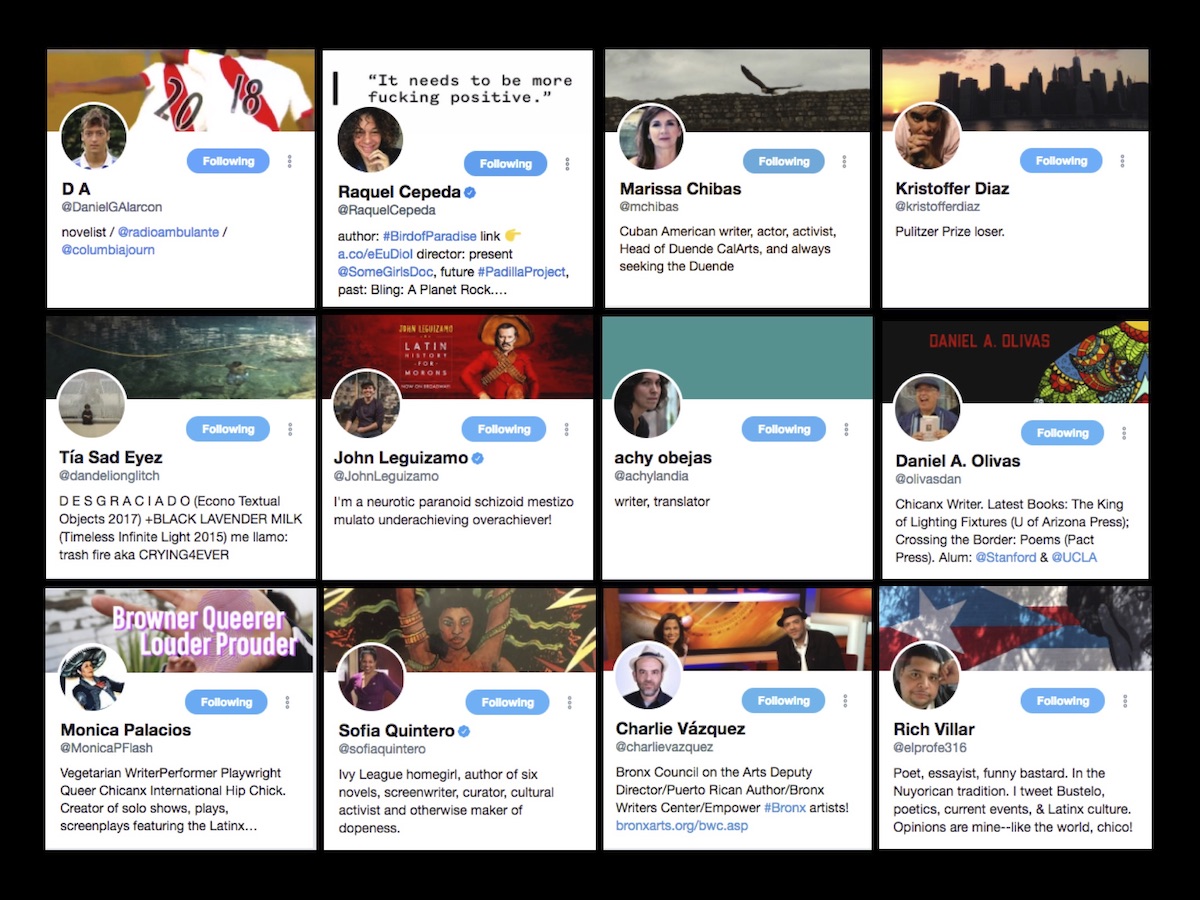

This essay engages in a comparative analysis of Miranda’s invocation of “for you” on Twitter with that of twelve other US Latinx writers with two goals: to identify broader key trends in the discursive strategies used on Latinx Twitter as well as to make the case for the urgent need to ethically document and archive contemporary Latinx Twitter production. I specifically highlight the digital work of Cuban American playwright Marissa Chibas, Puerto Rican poet Rich Villar, and Puerto Rican writer Charlie Vázquez on Twitter as a counternarrative to Miranda’s aesthetics. US Latinx cultural producers deploy a diversity of aesthetic forms when engaging Twitter as a discursive space. In the words of theater scholar Patricia Ybarra, there exists a “temptation” among academics to read US Latinx cultural production as “reveal[ing] an unmediated truth about US Latinx life,” which in turn leads them to look to such texts “primarily for content, without giving much attention to form.”4 My comparative approach to the landscape of US Latinx Twitter therefore seeks to avoid this ethnographic lens by addressing both the form and content of social media work by US Latinx writers.

Social Media, Surveillance, and Affect

How Miranda uses Twitter, the way in which he strategically blurs the boundaries between public and private life, is intimately connected to the platform’s surveillance and labor dynamics. Twitter’s homepage invites the reader to “see what’s happening in the world right now,” situating the social networking service as an entryway into a contemporary and global public sphere.5 The implication is that we will enter Twitter primarily as observers who will gain access to a big-picture perspective on contemporary events; however, the power dynamics behind one’s participation in this public sphere are more complicated than such advertising indicates. In defining the dynamics of our contemporary public sphere, I borrow from Christopher Balme’s The Theatrical Public Sphere, which conceptualizes it as a “discursive arena located between private individuals on the one hand and state bureaucracy and business on the other” and thereby “occup[ying] a crucial role in the functioning of so-called free or open societies.”6 Twitter forms part of a broader shift in terms of where public discourse now occurs. Indeed, Balme notes that “changing notions of spectatorship and publics” have accompanied the “explosion of Internet communication [and] use of social media,” while leading to questions about “production structures” and how they can be “controlled or manipulated.”7 Private corporations play a more central role in generating spaces for public discourse, with such spaces codified according to the logic of profit extraction. As Dorothy Kim argues in “The Rules of Twitter,” these platforms “have usurped mainstream media as the main and primary source of on-the-ground, archived, filtered, and live information.”8 The parameters that Twitter uses to structure discursive exchange matter. After all, as Dorothy Kim and Eunsong Kim note in “The #TwitterEthics Manifesto,” “Twitter is a closed, private corporation,” and, as such, its discursive world is motivated by profit.9 And yet, the lack of transparency makes it challenging to discern how the corporation dictates the terms of social engagement.

The domination of the public sphere by social media has blurred the boundary between cultural producer and consumer, in part because of how central surveillance is to the exchange of information that takes place on Twitter. When we enter Twitter, we are not merely watching the world “happen”; we ourselves are being watched. Surveillance is fundamental to the profit logic of social media, with the data extracted from the analysis of our behavior translated into the commodity for sale. Elizabeth Losh helpfully describes in Hashtag the way profit is generated, with social media companies “offering supposedly free content via targeted advertising and the sale of user data that depends upon intimate knowledge of users’ personal preferences, emotional sentiments, and social relations that had previously been unmonetized.”10 By extension, access to the “free” exchange of ideas on Twitter is given in exchange for the implicit surrender of our selves to corporate surveillance. Our understanding of surveillance, as Sydette Harry points out, has been historically defined as “an activity of Big Brother-style” governance, which limits our ability to perceive the “fannish adulation and social enmeshment” on social media as part and parcel of its profit logic.11 Surveillance on social media is essentially obligatory if one wants to engage in the public sphere. Harry provides a useful definition of surveillance that situates a lack of consent as integral to its power:

Surveillance is based on a presumption of entitlement to access, by right and by force. More importantly, it hinges on the belief that those surveilled will not be able to reject surveillance—either due to the consequences of resisting, or the stealth of the observance. They either won’t say no, or they can’t.12

On the one hand, we are invited by Twitter to feel entitled to access the world of others, while at the same time, the lack of transparency about what lies behind its interface means that we do not fully know how or who is entitled to derive profit from our discursive production online. Harry emphasizes that “as opting into surveillance becomes increasingly mandatory to participate in societies and platforms, surveillance has been woven into the fabric of our lives in ways we can not readily reject.”13 The unique network of shared intimacies that social media cultivates enables many marginalized peoples to thrive, which means that finding community online is essential to social survival. As such, the problem of surveillance is not one that can be easily avoided if one wants to be an engaged participant in public discourse, or to put it more simply, if one wants to find belonging and social support in this contemporary world. It is important to acknowledge, however, that while consent to surveillance is assumed by the platforms like Twitter, that does not mean it is actually given.

I am particularly interested in critiques of social media’s social surveillance logics that focus on how the exploitation of discursive production online is based on an emotional debt economy. The intersection of affect and labor on Twitter is best described by Lisa Nakamura in her essay “The Unwanted Labour of Social Media: Women of Colour Call Out Culture as Venture Community Management,” in which she explains that the profit logic of social media platforms relies on “crowd-sourced labour of internet users” and that such “labour is uncompensated by wages, [and] paid instead by affective currencies such as ‘likes,’ followers, and occasionally, acknowledgement or praise from the industry.”14 The labor is not merely compensated through “affective currency.” Venues such as Twitter become discursive spaces that are “fun, easy, and safe to use” because of producers whose “openness towards forming new relationships with strangers who want or need them” allow for “the provision of free advice.” While Nakamura aims to render visible the “feminised” and “devalued” labor of women of color on social media platforms, I also find her description of this unique labor market useful for understanding Miranda’s Twitter aesthetics.15 As a cultural creative who has strengthened his visibility through social media platforms such as YouTube and Twitter, Miranda is not part of this exploited class. Rather, he strategically makes intimacy and affect central to his discursive performance on Twitter, and in so doing, gains the social “recognition and responsibility” to lobby for his creative and financial investments.16 Miranda uses the affective dynamics of the debt economy on Twitter to accrue both social and economic capital.

In the spirit of Macarena Gómez-Barris’s call to “reorient our study toward the creative praxis and submerged perspectives that are found beneath or at the edge of the dominant political tide,” I have endeavored to offer a comparative analysis of Miranda, placing his Twitter production alongside that of other US Latinx authors.17 I will argue that Miranda’s use of Twitter differs from the way most US Latinx writers engage the platform, and for this reason, my engagement with those Latinx creatives also differs. While Miranda conceives of Twitter as a platform for self-promotion, I endeavor to be attentive to how the public profiles of other Latinx writers operate in a more minor key. With discursive production that focuses on activism, affective survival, and community-building, I consider these Twitter feeds to be governed by a different set of power dynamics. I believe that my citation practices require an acknowledgement of how their cultural production is vulnerable to exploitation within the affective marketplace of Twitter in a way that Miranda’s is not. For the writers whose tweets I wanted to reproduce in full here, I requested their permission to cite their work and, in so doing, I attempted to follow the directives for ethical academic work laid out by Dorothy Kim in her essay “Social Media and Academic Surveillance: The Ethics of Digital Bodies.” Kim condemns current practices of academic research that entail the harvesting of Twitter production by people of color, challenging the claim that such production is in the public dominion and therefore does not require “permission, consent, conversation, and discussion.” She emphasizes the surveillance logic of Twitter as a “panoptic medium” and “digital publics” that is “subject to the same problems of surveillance and ethics we find in geographical space.” By sharing a draft of this essay with Marissa Chibas, Rich Villar, and Charlie Vázquez prior to publication and requesting permission to cite their tweets, I hope that I express respect for the labor that went into producing the “digital intellectual property” of US Latinx creative writers.18 This means not merely publishing their tweets with their consent, but sharing with them the context within which I am placing their work, providing them with the opportunity to speak back to my research and writing process as well as to request the exclusion of their tweets from analysis.

When I share with literary studies colleagues my decision to obtain consent, I often get the response that the process for citing tweets should be similar to citing a published literary work. We do not ask a creative writer for permission to cite their literary production, so why should we ask for permission to cite a tweet? I want to reiterate here that the “public” text of Twitter production is governed by power dynamics different from those of the traditional object of literary study, a published book. Shoshana Zuboff discusses a similar false equivalency in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, while detailing the unexpected implications of Section 230 from the 1996 Communications Decency Act. She observes that a journalist translated the import of this section by noting that an internet company should not be sued for the malicious content they publish just as a public library would not be sued for holding a copy of a controversial book. Zuboff helpfully challenges this comparison by underscoring how an individual’s interaction with a website as public space does not operate in the same way as with a public library, the primary difference being that an individual interacting with a website becomes a resource to be commodified and exploited:

Under the regime of surveillance capitalism, content is a source of behavioral surplus, as is the behavior of the people who enter the content, as are their patterns of connection, communication, and mobility, their thoughts and feelings, and the meta-data expressed in their emoticons, exclamation points, lists, contradictions, and salutations.19

By contrast, the text we researchers find on a bookshelf in the library is not tagged with “the records of anyone who may have touched it and when, their behavior, networks, and so on.” My scholarly relationship to the production of Latinx writers on Twitter therefore cannot be the same as my relationship to their literary production of published poetry, plays, and fiction. Their tweets are part of a surveillance marketplace, and I cannot simply extricate them or myself from that market dynamic in order to perform my research. Rather, my research is enabled and complicit with the forces that commodify their creative production online. Much of the meaning I can ascribe to their tweets is facilitated by the fact that social media giants—or as Zuboff calls them, the surveillance capitalists—have created a platform that functions as a “diamond mine ready for excavation and plunder, to be rendered into behavioral data and fed to machines on their way to product fabrication and sales.”20

At the same time, I must acknowledge that the pseudo-restorative justice process I embark on to acknowledge the labor of US Latinx writers on Twitter is aspirational. That process is always a failure because there is no real way to decouple the tweets from the surveillance dynamics that they are born into. In addition, I came across Dorothy Kim’s work on ethics and Twitter after I had already performed the research and writing stages for this project. I pulled tweets, generated charts, and analyzed these materials before I was able to find the language to articulate the profound discomfort I experienced while doing all this. To my friends and colleagues, I apologetically described myself as a “lurker” on Twitter because I had a Twitter account but no feed; I was only there to observe out of academic interest. At the same time, I felt that I was an interloper, that I was trespassing on conversations that did not necessarily imagine me as a listener. I encountered Kim’s “The #TwitterEthics Manifesto” as part of a course she co-taught with Angel Nieves at the Digital Humanities Institute held at the University of Victoria in June 2019. Reading it, I was so grateful to finally have a language by which to explain why and how the research process disturbed my conscience. It is one thing to gain that confirmation, but it is quite another to actually do something about it. Frankly, my first impulse was to just chuck all this research and writing in the garbage and walk away. In some ways, I know that my desire to cut ties with this project is also based in a profound insecurity about my ability to do this work, by which I mean academic work, literary studies work, digital humanities work. I decided that I would be transparent about my process and attempt a recuperative form of justice anyway by sharing the essay with Marissa Chibas, Rich Villar, and Charlie Vázquez, US Latinx writers who are less visible in certain fields of academia. I did not request permission from Lin-Manuel Miranda because of the way he frames his feed as a mainstreaming tool as well as a source for his artistic and fundraising projects. Understandably, the reactions of Chibas, Villar, and Vázquez to my queries was mixed, and I share my process for obtaining consent from those writers in order to at least offer a cautionary tale of what not to do when you embark on Twitter research, which is: do not start the process for obtaining consent after you begin data collection and analysis because minimizing harm after the fact is impossible. Obtain consent before you begin.

I contacted Chibas, Villar, and Vázquez via e-mail during September 2019, requesting permission to cite their tweets in my essay. In the message, I explained my project and my goal of publishing it in an academic journal, while also sharing an essay draft so they could assess how I framed and analyzed their tweets. I closed the message by stating, “If you don’t reply to my query by October 15th, I’ll assume that your preference is that I do NOT cite your tweets.”21 My choice of an “opt-in” process was informed by the collaborative essay “The Ethical Challenges of Publishing Twitter Data for Research Dissemination,” shared by my colleague Christian Howard. The essay’s coauthors understand the primary challenge of Twitter research to be grounded in how scholars address “fundamental ethical principles such as the minimization of harm and the value of informed consent.” The researchers explain that with the “collection of Twitter data, informed consent for data collection is typically based on user acceptance of its Terms of Service.”22 Of course, “social media users are unlikely to read or remember” these documents for social media platforms, “undermining the assumption that informed consent has been given.”23 Owing to an “absence of consensus” about best practices for consent, I chose to follow the opt-in model because I would be able to assume a nonreply as an absence of consent.24 Chibas and Vázquez both replied to my queries and e-mailed their permission, while Villar did not reply to two separate e-mail requests. Chibas responded on 29 September with the message, “I briefly looked over your doc and it seems just fine to me. That is quite a substantial piece you are working on.” Vázquez replied on 20 September, saying, “How very cool…go ahead and use what you would like. Thanks for including me.”25 In addition to incorporating and analyzing the tweets by Chibas and Vázquez, I embed in this essay the gaps produced by Villar’s nonconsent so that my writing symbolically evokes the gaps in my research argument now that my citation of Villar is not ethically possible—and to document my failure to request the consent of the rest of the US Latinx writers I include here. I use black highlighter to render visible the redacted analysis and Villar tweets in the hope that it more powerfully conveys the cautionary tale I want to tell about the Twitter data collection process and its inherent surveillance.

Digital Tools and Methodology

Since May 2017, I have been accumulating archives of tweets for more than one hundred Latinx creative writers, from poets to playwrights, using the programs TAGS Archiver and Twitter Archiver. I did not request permission from these writers when I set up the automatic process for collecting tweets. In addition to incorporating creative producers of different genres, the scope of the project is pan-ethnic, drawing from the various communities that inform Latinidad within the United States: from the historical populations of Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans, to relatively more recent diasporas of the Dominican Republic, Central America, and South America. I used Voyant to visualize word patterns and social networks on US Latinx Twitter. Additionally, I created a searchable archive using the program Oxygen and then converted a portion of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Twitter archive into HTML (hypertext markup language), posting online a temporally limited collection of “for you” tweets that appeared from May 2017 to January 2018.26

With the aim of distinguishing the unique qualities of Miranda’s Twitter use, I created text files for over forty other Latinx writers using TAGS and Twitter Archiver so as to perform a comparative analysis. These writers included Chantel Acevedo, Daniel Alarcon, John Manuel Arias, Ruth Behar, Richard Blanco, Nao Bustamante, Daisy Cabrera, Jennine Capó Crucet, Joy Castro, Raquel Cepeda, Marissa Chibas, Angie Cruz, Migdalia Cruz, Jaquira Díaz, Kristoffer Diaz, Angel Dominguez, Yalitza Ferrera, Coco Fusco, Guillermo Gomez Peña, Laurie Guerrero, Daisy Hernandez, Cristina Henriquez, Quiara Alegria Hudes, John Leguizamo, Aurora Levins Morales, Natalie Lima, Valeria Luiselli, Urayoan Noel, Achy Obejas, Daniel Olivas, Monica Palacios, Daniel Peña, Willie Perdomo, Sofia Quintero, Lilliam Rivera, Awilda Rodríguez Lora, Isaias Rodriguez, Esmeralda Santiago, Caridad Svich, Hector Tobar, Charlie Vázquez, and Rich Villar. It is worth noting here that there are several generations of contemporary Latinx writers who either do not have Twitter accounts (like Sandra Cisneros, Julia Alvarez, and Ana Menéndez) or they have a negligible presence (such as Junot Díaz and Ana Maurine Lara). I winnowed down this initial list to a more select group of authors by first determining who established a significant audience for their Twitter production. In selecting my corpus of writers to compare with Miranda, I also kept in mind how prolific these writers were, with the goal of selecting those who maintained an active presence on Twitter by posting original tweets or retweeting.

| US Latinx Creative Writer | Username | Number of Followers |

|---|---|---|

| Lin-Manuel Miranda | @Lin_Manuel | 1,800,000 |

| John Leguizamo | @JohnLeguizamo | 708,000 |

| Daniel Alarcón | @DaniekGAlarcon | 193,000 |

| Charlie Vázquez | @charlievazquez | 14,600 |

| Raquel Cepeda | @RaquelCepeda | 11,700 |

| Sofia Quintero | @sofiaquintero | 5,835 |

| Kristoffer Díaz | @kristofferdiaz | 4,439 |

| Daniel Olivas | @olivasdan | 3,514 |

| Rich Villar | @elprofe316 | 2,270 |

| Achy Obejas | @achylandia | 2,107 |

| Monica Palacios | @MonicaPFlash | 758 |

| Angel Dominguez | @dandelionglitch | 635 |

| Marissa Chibas | @mchibas | 627 |

Figure 3. Comparison by number of followers.

| US Latinx Creative Writer | Username | Numbers of Tweets |

|---|---|---|

| John Leguizamo | @JohnLeguizamo | 4,737 |

| Lin-Manuel Miranda | @Lin_Manuel | 4,466 |

| Daniel Olivas | @olivasdan | 4,214 |

| Achy Obejas | @achylandia | 3,688 |

| Sofia Quintero | @sofiaquintero | 2,261 |

| Monica Palacios | @MonicaPFlash | 1,924 |

| Kristoffer Díaz | @kristofferdiaz | 1,726 |

| Angel Dominguez | @dandelionglitch | 1,694 |

| Daniel Alarcón | @DaniekGAlarcon | 1,655 |

| Charlie Vázquez | @charlievazquez | 1,629 |

| Raquel Cepeda | @RaquelCepeda | 1,014 |

| Rich Villar | @elprofe316 | 590 |

| Marissa Chibas | @mchibas | 457 |

Figure 4. Comparison by number of tweets.

The resulting list of twelve writers is therefore a cross-section of those Latinx authors with the most followers and the most active tweet production during approximately a six-month window, from May to November 2017. After selecting these twelve authors for the comparative analysis with Miranda, I cleaned the text files of the Twitter archives by removing duplicates, uploading them to Voyant, and editing the list of stopwords in order to visualize the patterns and distinguishing features of each Latinx writers’ Twitter use.

Figure 5. Twitter profiles of twelve Latinx writers.

Voyant’s term-analysis function and trend-line graph help us compare the Twitter data for Miranda and the twelve other writers. I analyzed the top twenty-five most frequently occurring words in the archive using Voyant. Normally, the word “you” is listed as a stopword, so it gets pulled out of analysis when analyzing a large corpus. I decided to remove from the stopword list terms of self-representation (“I,” “am,” “be”) and affiliation language (“you,” “your,” “we,” “us,” “our”) in order to get a better picture of the distinctive uses of “you” in Latinx Twitter. I also added common usernames, tags, and handles to the stopwords list in order to center the Voyant analysis on the language content of the tweets. The list of the top twenty-five most frequently occurring words in the archive therefore highlighted the terminology used to reference audience and community. A distinctive feature of the data for the twelve Latinx writers is the predominance of terms such as “we,” “Trump,” “people,” and “white,” which reflect the centrality of contemporary political discourse and cultural critique on their Twitter feeds. Latinx writers are using Twitter as a space to address President Donald Trump’s nationalist platform and respond directly to the president’s stoking of racism and anti-immigrant fervor. There is also a discursive balance present between the use of individualist terms such as “I,” “my,” and “me” and references to the communal with “we,” “us,” and “our.” While “Trump” is a popular term found in Miranda’s tweets, it is not in his top twenty-five words. Miranda’s vocabulary is distinctive because of the prevalence of earnest intimacy terms (“good,” ‘thanks,” “love,” “like”) and time (“day,” “morning,” “night”). The relationship between Miranda’s self and an individual other dominates the wordcloud, with the references to “I,” “I’m,” “my,” and “me” alongside “you” and “your.”

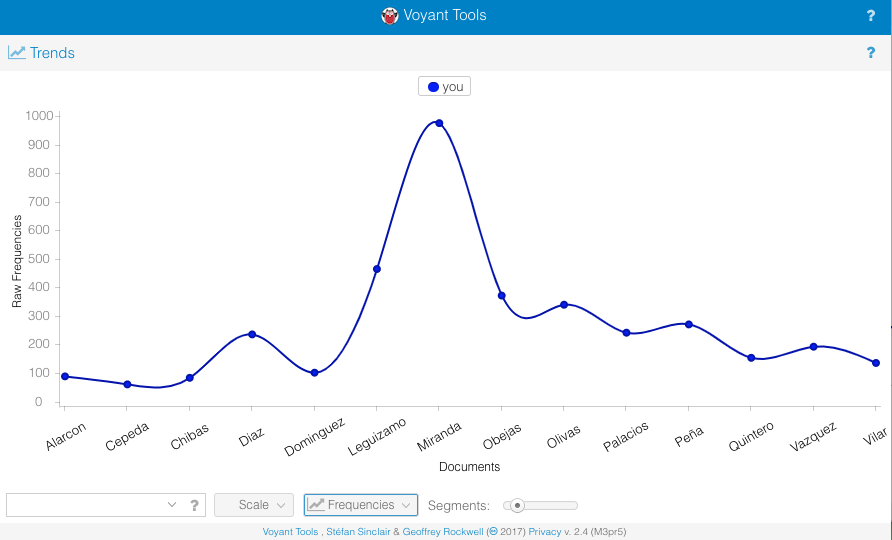

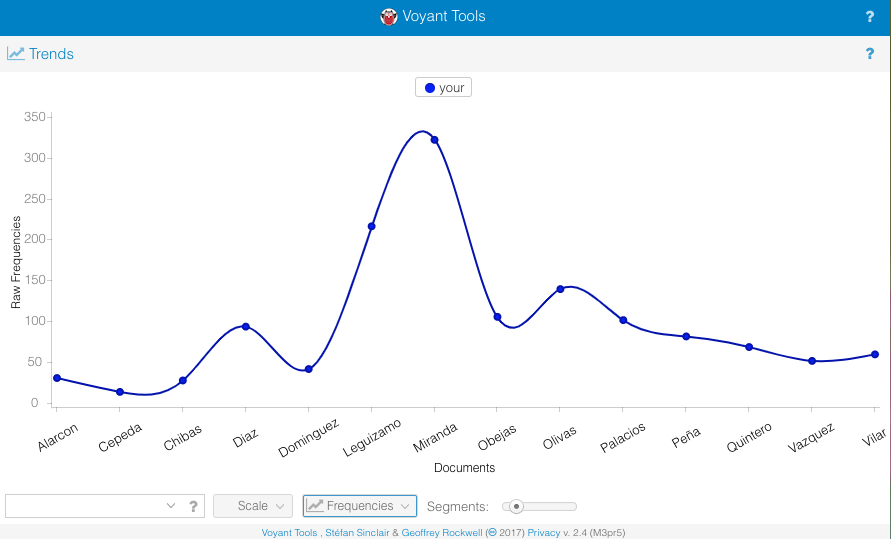

The centrality of “you” to Miranda’s Twitter rhetoric is made clearer in the line graph comparison with other writers. Looking at the raw frequency of “you” and “your,” reveals that Miranda’s direct references to his Twitter audience are consistent and distinctive. By contrast, the references to a collective or kinship with followers, such as “we” and “us,” reflect a more level playing field amongst the group of thirteen writers.

Figure 6. The raw frequency of you in the corpora of thirteen writers.

Figure 7. The raw frequency of 'your' in the corpora of thirteen writers.

Figure 8. The raw frequency of 'we' in the corpora of thirteen writers.

Figure 9. The raw frequency of 'us' in the corpora of thirteen writers.

Miranda’s self-representation and affiliation on Twitter relies upon a discursive labor, producing original content and emotional affirmation for his followers. In order to compare Miranda’s rhetorical strategies with those of the twelve other Latinx writers, I focused on the use of the specific phrase “for you,” during the period of 10 May and 15 November 2017. Analyzing the use of “for you” in a combined archive of over thirty-three thousand tweets facilitated a much more manageable review process for me as the lone investigator of the project. With this corpus, I removed all the retweets, focusing solely the authors’ original production of messages and therefore direct references to audience. While statistically less significant than the use of “you,” the “for you” archive permitted a close reading of individual tweets and a more in-depth comparison of discursive strategies. I correlated the number of “to you” references with the total number of tweets produced during the May to November time period. It is worth pointing out the contrast that the chart reveals between Miranda and John Leguizamo, who produced a similar number of tweets during the same time period but had significantly fewer mentions of “for you.” Such a divergence reveals that while Miranda and Leguizamo have similar rates of productivity and engagement with their Twitter followers, the “for you” usage indicates a divergent set of writerly strategies for engaging that audience. The writers who use “to you” at rates to Miranda are authors who have a significantly smaller set of followers and are less active on Twitter: Cuban American playwright Marissa Chibas, Puerto Rican poet Rich Villar, and Puerto Rican writer Charlie Vázquez.

| US Latinx Creative Writer | Username | Number of Tweets | Percentage of Tweets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marissa Chibas | @mchibas | 7 out of 457 | 1.53% |

| Lin-Manuel Miranda | @Lin_Manuel | 61 out of 4466 | 1.37% |

| Rich Villar | @elprofe316 | 4 out of 590 | 0.068% |

| Charlie Vázquez | @charlievazquez | 6 out of 1629 | 0.037% |

| Raquel Cepeda | @RaquelCepeda | 3 out of 1014 | 0.030% |

| Angel Dominguez | @dandelionglitch | 4 out of 1694 | 0.024% |

| Sofia Quintero | @sofiaquintero | 5 out of 2261 | 0.022% |

| John Leguizamo | @JohnLeguizamo | 9 out of 4737 | 0.019% |

| Monica Palacios | @MonicaPFlash | 2 out of 1924 | 0.001% |

| Kristoffer Díaz | @kristofferdiaz | 1 out of 1726 | 0.0006% |

| Daniel Alarcón | @DaniekGAlarcon | 1 out of 1655 | 0.0006% |

| Daniel Olivas | @olivasdan | 2 out of 4214 | 0.0005% |

| Achy Obejas | @achylandia | 1 out of 3688 | 0.0003% |

Figure 10. A comparison of 'for you' usage in original tweets between May 10, 2017–Nov. 14, 2017 (with retweets removed).

Concentrating on the phrase “for you” as a lens of comparison makes explicit a tweet’s reference to a relational dynamic. “For you” often connotes a presentation or act of gifting, whereby one individual creates or assembles something for another. More importantly, the phrase functions as an indicator for how the writer imagines and situates the audience of followers. By close reading the tweets in the corpus, we see that the Twitter usage trends of cultivating intimacy and articulating an activist politics are expressed using different strategies.

| Directed intimacy with general Twitter audience | 46 |

| production of original product/mixtapes | 15 |

| advice/instruction | 10 |

| self-promotion | 9 |

| gratitude | 8 |

| acknowledge/respond to demand for products | 1 |

| Activism | 7 |

| critique of Trump as “you” | 2 |

| empathy reaction to tragedy | 3 |

| support of DREAMers as “you” | 1 |

Figure 11. A breakdown of sixty-five 'for you' tweets by Miranda.

| Activism | 22 |

| gratitude for activism of specific others | 10 |

| critique of Trump as “you” | 8 |

| critique of Trump supporters | 4 |

| Gratitude to specific creative producers | 14 |

| Directed intimacy with general Twitter audience | 8 |

| offer/request emotional support | 4 |

| advice for work/writing/health | 3 |

| reading recommendation | 2 |

Figure 12. A breakdown of forty-five 'for you' tweets by twelve Latinx writers.

Miranda uses Twitter to articulate concerns similar to those of other Latinx writers, namely, using the “you” to relate to a general audience of Twitter followers or to articulate an activist politics. The difference is that the percentage of tweets dedicated to these interests is flipped. Miranda dedicates 75 percent of his tweets to cultivating intimacy with a general Twitter audience and 11 percent on activism-related topics. As a group, the twelve Latinx writers dedicate 48 percent of their tweets to activism, 31 percent to expressing gratitude to specific creative producers (other writers, for example), and 17 percent to cultivating intimacy with a general Twitter audience. A different relationship also emerges between their Twitter aesthetic and activism. The phrase “for you” is most often used to refer to a specific individual, as opposed to the entire audience of followers. Additionally, these Latinx authors do not produce original content on Twitter. Rather, they network with particular individuals, retweeting in order to amplify voices of others.

Activism Online: Marissa Chibas, Rich Villar, and Charlie Vázquez

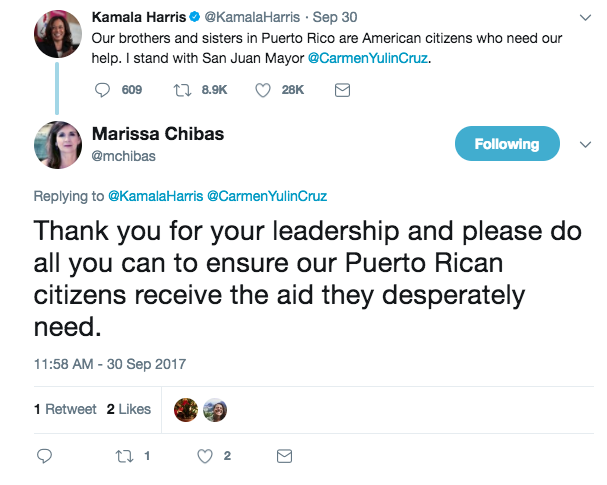

The activism of US Latinx writers finds expression via their messages of gratitude for a specific person’s actions or in critical posts about President Trump and his followers. Cuban American playwright Marissa Chibas’s feed serves as one example of how Latinx writers use Twitter predominantly as a space for political activism as well as to build constructive relationships with specific progressive individuals.

| Date of Tweet | @mchibas | Reply to |

|---|---|---|

| Sept. 30, 2017 | Thank you for your leadership and please do all you can to ensure our Puerto Rican citizens receive the aid they desperately need. | @KamalaHarris @CarmenYulinCruz |

| Sept. 26, 2017 | Thank you for your continued leadership. | @BarackObama |

| Sept. 23, 2017 | My Equinox move for healing and restoration. For you my friends. #weneedtomove We Need To Move Together #wemove [video] | |

| Sept. 22, 2017 | Mildred I am so happy and relieved for you. Un abrazote! Pensando en ustedes y querido Puerto Rico. | @mredruiz |

| July 30, 2017 | They weren’t there for you 45, you were supposed to be there for them. | @DonCheadle |

| June 21, 2017 | Thank you for your vigilance, foresight, and leadership @RepAdamSchiff. We need the whole truth. | @RepAdamSchiff |

| May 31, 2017 | Thank you for your leadership. | @kdeleon @realDonaldTrump |

Figure 13. 'For you' tweets by Chibas.

Within this select group of tweets, we see Chibas replying in support of US senator for California Kamala Harris; the mayor of San Juan Puerto Rico, Carmen Yulín Cruz Soto; former president Barack Obama; the actor Don Cheadle; US representative for California Adam Schiff; and California state senate president Kevin de León. These are public figures rather than people whom Chibas knows personally. Her tweets therefore seek to foster a productive dialogue with political actors, not simply to network with them but to reaffirm her commitment and support. She also includes President Trump on her reply to de León as a means of confirming de León’s critique of the administration’s decision to pull out of the Paris climate accord.

Such tweets represent Chibas’s efforts to intercede in political discourse concerning the US government’s response to Puerto Rican disaster relief as well as more general critiques of President Trump.

When tweets work to build intimacy with a general audience, the creative writer is posting messages to request emotional support or advice, as we can see in the case of Puerto Rican poet Rich Villar. His “for you” tweets fall into the same top three categories as the tweets of the other Latinx writers: critiques of President Trump, requests for support, and expressions of gratitude to specific creative producers. xxxxxx’x xxxxxx xx xxxxx xxx xxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx xxxxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxxxx’x xxxxxx; xxx xxxxxxx, xx xx xxxxxx 2017 xxxxx xx xxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx xx “xxxxx xxxx xxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xx xxx xxxxxx xxxxxx xxx xx xxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxx,” xxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxx-xxxxxx xxxxxxxx xx xxx xx xxx xxxxxxxx. xxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxx xx xxxxx’x xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxx xxx 2017 xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxx xxx xx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx, “[x xxxx x] xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxx xxx xxx xx xxxx.” xxx xxxxx xx xxxxx xxxxxx xx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxx, xxxxxxxxxx x xxxx xx xxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxx, xxxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxxxx’x xxxxx xx xxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx.

| Date of Tweet | @elprofe316 | Reply to |

|---|---|---|

| 08/17/2017 | …xxx xxxxxxx xxxxx xxx xx xxxxx xxx xxxxx-xxxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxx xxx? | @realDonaldTrump |

| 08/16/2017 | x xxxx x xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxx xxx xxx xx xxxx. xxxxx://x.xx/00xx0xxxx1 | @realDonaldTrump |

| 08/05/2017 | x’xx xxxx xxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxx xxxx xx xxxxx xxx xxx x’x xxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxxx, xxxxxxx, xxxxxxx, xxxxxx, xxxxx xx xxx xxxxx…xxxxxxxx! | |

| 08/05/2017 | xxxxx xxx! x xxxxxxxx xxx xx xxxxxxx xxx x’x xxxxxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxx. | @gionvalentine |

Figure 15. 'For you' tweets by Villar.

xx xxxxxxxx, xxxxxx’x xxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxxxx xxxxx x “xxxxx xxx” xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx “xxxxxxx, xxxxxxx, xxxxxxx, xxxxxx, xxxxx xx xxx xxxxx…xxxxxxxx!” xxxx xxxx xxxxxxxx x xxxxxxxxx xx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxx xxx xxxx xxxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxx xxx xxxx xx xxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxx xxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx. xxxxxxxxxxxx, xx xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx xxx xxx xxxxxxxx “xxxxxx.” xxxxxx’x xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxx xxxxxxx xxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxx xx xxxx xx “xxxxx” xxxxxx xxxxxxx. xxx xxxxxxxx xx xxxxxxxxx xxxxx xx xxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx x xxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxx xx xxxxx xxx xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxx xx xxx xxxxxx xxxxxx..

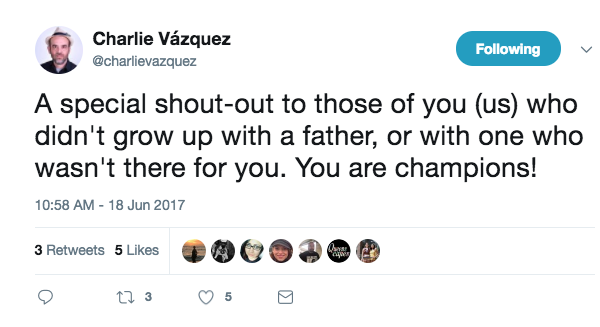

When Latinx writers imagine their followers as a cohort, that “you” carries a communal reference. For instance, Puerto Rican author Charlie Vázquez’s “shout-out” parenthetically translates the “you” to “us” in imagining the shared familial context of absent fathers.27

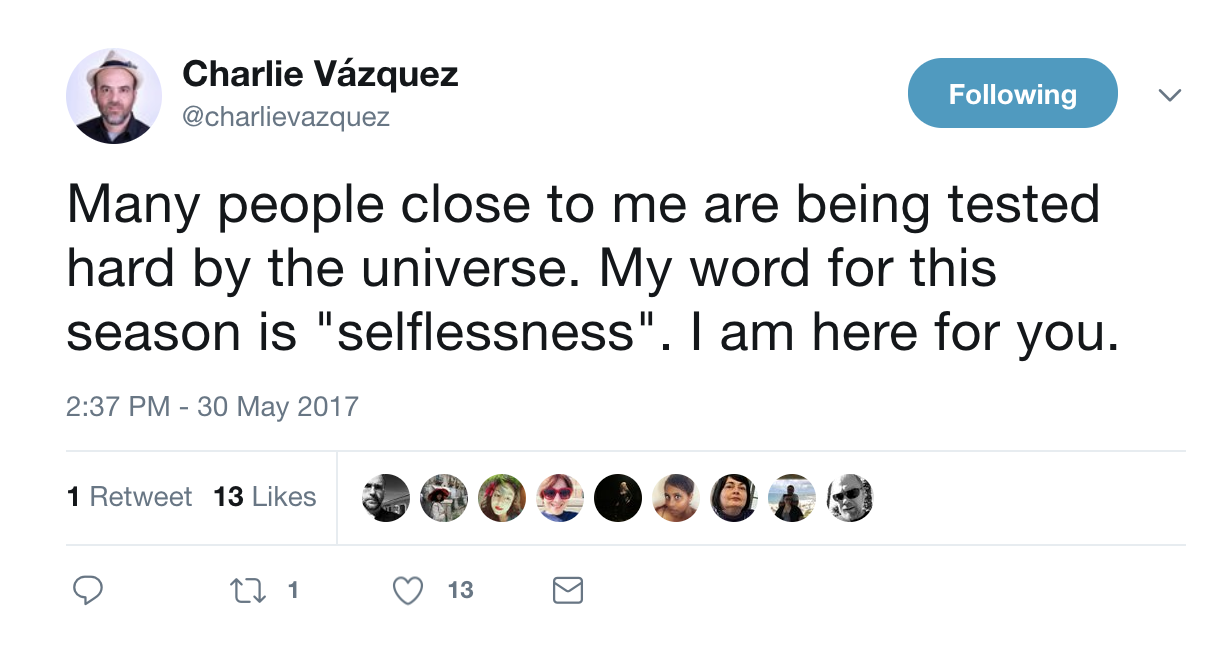

Similarly, his tweet offering support to people “close” to him who “are being tested” aims to publicly display his offer, “I am here for you.”28 The transition from “people” to “you” shifts a third-person subject into the second person, establishing an intimate relationship on the platform of social media. At the same time, this declaration seeks to articulate a specific ethics to the general audience of followers, implying that they too should adopt “selflessness” as the “word for this season.” Miranda is not alone in his strategic invocation of intimacy on Twitter via the phrase “for you.” Nonetheless, he is perhaps the Latinx writer who most actively cultivates a Twitter persona using a habitual practice of performing and modeling intimacy and affect.

Lobbying, the Miranda Family Business

Critics of US Latinx literary studies often situate Lin-Manuel Miranda as part of a broader history of US Latinx political activism. For example, in an essay summarizing the development of US Latinx theater, Ricardo L. Ortíz offers Miranda as an example of how US Latinx creatives “have not only made their mark thanks to unprecedented critical and commercial success, but have done so while adhering uncompromisingly (each in its own way) to a vision of US political, social, and cultural life within which Latinos and other people of color figure not just prominently but centrally.”29 Miranda’s emblematic status as both artist and activist is credited to how he foregrounds US Latinx life and bodies on stage. While I am interested in troubling the progressive potential of representational politics, I am limiting myself here to complicating the notion of a shared vision of activism, specifically by distinguishing between how US Latinx writers and Miranda deploy Twitter as a tool for activism. In terms of their rhetoric, US Latinx writers draw on a vocabulary of collective action in their tweets, imagining the relationship between their individual self and a “we” of followers. Miranda, on the other hand, focuses on imagining his audience on Twitter in terms of an individualistic “you.” Miranda thus frames his tweets as an interaction or conversation between individuals, which in turn facilitates his calls for financial activism, requesting that his followers donate money toward causes he values. Before delving into concrete examples of how his deployment of “you” differs from that of other US Latinx writers, I contextualize Miranda’s discursive strategies within a unique family history of neoliberal activism. By neoliberal, I mean that the Miranda family views activism in terms of the accumulation of capital, with money as the primary means of building political power and effecting social change.

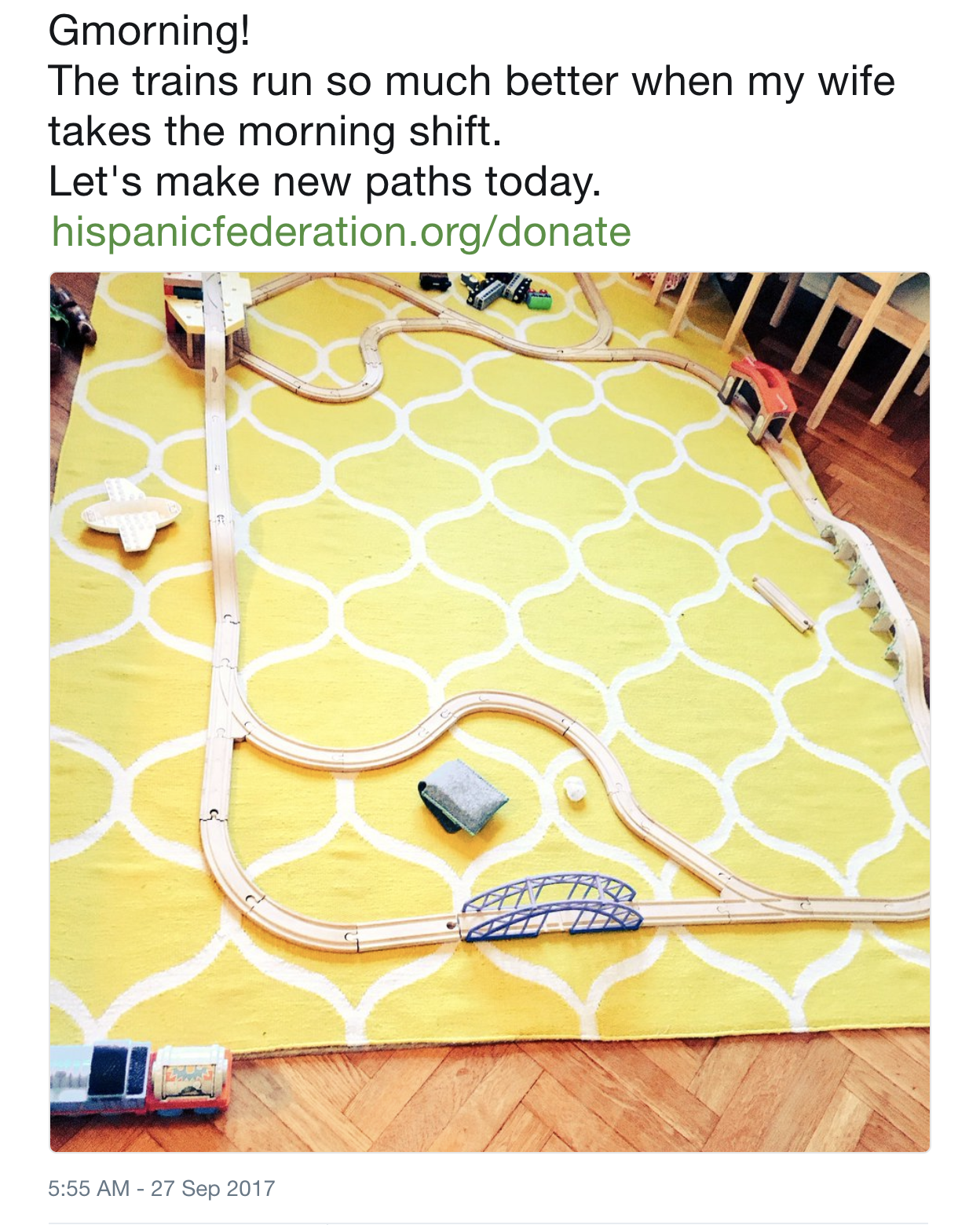

Miranda mobilized his followers to support, through financial donations, the hurricane recovery efforts in Puerto Rico, for example, with the #AlmostLikePraying benefit song project, which involved the production of original content (the song, video, and documentary). Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on 20 September 2017. On 6 October, Miranda released the song “Almost Like Praying” and the Spotify playlist Puerto Ricans for Puerto Rico as fundraising tools for recovery relief. All proceeds from downloads and streams of “Almost Like Praying” go the Hispanic Federation’s disaster relief fund to aid Puerto Rico.30 Miranda’s Twitter feed was a key method in marketing the benefit song project and an overview of his tweets for that year reveals how promoting it dominated his feed. During the period of May 2017 to February 2018, the top hashtags for Lin-Manuel Miranda’s feed were #Ham4Ham (133), #AlmostLikePraying (73), #ForPR (39), #PuertoRico (25), #PorPR (25), #Hamildrop (25), #AmWriting (20), #HamForHam (18), and #HamiltonLDN (15). The hashtags evoke the enthusiasm over all things Hamilton, which was enhanced by the musical’s reiteration as its own preshow in Ham4Ham.31 The intertwining of the musical’s marketing with the recovery activism hashtags is also evidenced in Miranda’s return to the title role in January 2019, ostensibly to generate tourism for hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico.

In addition to the rhetorical strategies that Miranda typically uses to build affective alliances with his Twitter followers, a family background of neoliberal activism is central to analyzing Miranda’s response to the hurricane Maria recovery efforts. In an exemplary fundraising tweet on 5 October 2017, Miranda uses the first-person “I” to engage a “ya’ll” of followers to financially commit themselves to supporting the recovery project by donating to nonprofit organizations such as MoveOn.org, a 501(c)(4), and the Hispanic Federation, a 501(c)(3).32 Miranda’s support of the Hispanic Federation in particular requires some contextualization, since his father Luis A. Miranda was a cofounder of the nonprofit in 1990 and served as its first president. Ethical concerns have long been raised about the relationship between Luis Miranda’s lobbying group MirRam and the Hispanic Federation.33 At the least, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s centering of the Hispanic Federation as a key player in the Puerto Rican hurricane recovery efforts can be interpreted as relying on similar a marketing dynamic and rhetoric to that of his self-promotion tweets.

Asking followers to make financial commitments or to contribute their volunteer labor requires mobilizing a community with whom an artist has weak ties, people who are not part of his or her immediate personal or professional network. Miranda’s calls for political or humanitarian action require the cultivation of intimacy with a community who will primarily respond with financial investment: buying music or making donations.

Miranda invests in a specific type of political action that is deeply rooted in the model of what I am choosing to call the Miranda family business: lobbying. In 2015 the veteran Puerto Rican reporter Juan González published in the New York Daily News an article about “the huge role” of the Miranda family in “nurturing” Miranda, whom González refers to as “this new genius of our stage.” He notes that Miranda’s father, Luis A. Miranda Jr., has been a “well-known leader in the Latino community” since he worked in Mayor Ed Koch’s Democratic administration, which governed the city from 1977 until 1989. González also reveals that Luis Miranda’s private political consulting firm, the MirRam Group, “has handled much of his son’s schedule since Lin-Manuel’s breakthrough Tony-winning musical In the Heights in 2008.” For González, Hamilton’s representation of the political landscape during the American Revolution is drawn from the younger Miranda’s familial experience: “As for how those politicians wielded power, Miranda learned from his dad.” He quotes Miranda’s own reflection as a fly on the wall for political strategy sessions: “I was the little kid drawing in the corner when my father was in all those meetings.”34 In other words, Miranda was in the room where it happens, one of the many private spaces where political actors make decisions about public policy and political strategy.

The #Ham4All challenge of June 2017 is a useful precursor to the marketing and activism web of the #AlmostLikePraying benefit song.35

Miranda asked fans to post videos of themselves singing to Hamilton songs after donating to the Immigrants: We Get the Job Done Coalition. The Hispanic Federation project’s name was derived from the lyrics of the song “Immigrants: We Get the Job Done” on the Hamilton Mixtape album that Miranda released in December 2016. In 2017, the federation adopted this catchphrase as the name for its alliance of nonprofit organizations addressing the needs of US Latinx communities.36 As previously mentioned, one of the Hispanic Federation’s cofounders is Miranda’s father, Luis Miranda. According to a 2014 newsletter by the National Institute for Latino Public Policy, the elder Miranda was installed as the first president of the nonprofit Hispanic Federation in 1990 “through the direct intervention of then NYC Mayor Ed Koch”: “Miranda had served as Koch’s Hispanic Advisor, a position that brought him much criticism from the Puerto Rican community that found Koch’s neoconservative policies antithetical to its interests.”37 Also mentioned earlier, all the proceeds of the 2018 #AlmostLikePraying campaign go to the Hispanic Federation. In 2000, Luis Miranda left the administration of the Hispanic Federation (although as recently as 2014 he remained listed as a paid lobbyist) to head the consulting and lobbying firm MirRam Groupa along with former New York City assemblyman and Democratic chairman Roberto Ramirez. Based on the research CityLimits performed in 2013 via New York City’s campaign finance database, MirRam was identified as one of the top six firms that “earned more than half a million dollars for campaign work.”38

The musical Hamilton plays an important role in facilitating the influence of a familial political network that is housed in the organizations of the Hispanic Federation and the MirRam Group. For example, MirRam “quietly created The Hamilton Campaign Network as a sister company to consult on state and city campaigns.” A MirRam spokesman explained that the “name is topical with all of the renewed political interest on Hamilton as a historical figure.” As noted by the Daily News, “The idea to separate out the lobbying and communications work of MirRam from the campaign work now done by Hamilton [Campaign Network] comes at a time when how Albany operates has come under increasing criticism and investigations.”39

While the collaboration of consulting and campaign organizations is legal, ethical questions have been raised about the undue influence such firms have by helping elect officials and then proceeding to lobby those same politicians. Access and influence are the top priorities of lobbying groups and Miranda’s Twitter aesthetic mobilizes his followers’ emotional capital and financial investment into specific political priorities that also further advance the Miranda family’s political networks. For example, just a day after Hurricane Maria’s landfall, Miranda casually integrated a recommendation for donations to be directed toward the Hispanic Federation “in the meantime.”40 No explanation is given in the tweet for why the Hispanic Federation is chosen as Miranda’s stopgap measure; however, a family history of connections to the organization certainly makes clear that this remark is strategic. The intersection of art and politics, emotional and financial lobbying, is developed further in a tweet that follows that same week, accompanied by a photograph of Miranda’s son’s toy train set, which provides the metaphor for donations to Puerto Rican recovery efforts.41 Miranda weaves a rhetoric of intimacy, using his good morning greeting to paint a picture of his domestic sphere, the toy train as a visual for his wife’s daily commute. The private is made public in order to gather his followers into a collective “we” that will similarly embark on “new paths” by donating to the Hispanic Federation. That call for donations was incredibly successful. As the New York Times noted in December 2018, “After the hurricane, the Mirandas helped raised $43 million for the Hispanic Federation’s hurricane relief fund.”42 Miranda’s reliance on the Hispanic Federation as his primary avenue for donations after Hurricane Maria’s devastation can be credited to family lessons learned on the campaign trail—that it is best to use an established network of contacts. Despite the intimacy cultivated by Miranda on his Twitter feed, the personal historiography of the Hispanic Federation is something Miranda does not tweet about, even though this relationship is by no means a secret but one that can be easily discovered with a mere Google search. When the relationship between Miranda and his family is acknowledged, it is done uncritically and without a sense of how it might impact the focus of his philanthropy and even benefit his family financially.43

The Guy Who Makes You (Feel) Things: Lin-Manuel Miranda

The bonds of virtual intimacy are accomplished via Miranda’s rhetorical labor as emotional caretaker and as a DJ, a musical mood producer, for his Twitter followers or, as his bio profile in January 2018 declared, the guy who is “making you things.”44

Miranda’s unique use of affiliation language builds an affective or emotional intimacy between his individual self “I” and communal “you” of followers. The aesthetic of intimacy provides a foundation for political activism on Twitter, mobilizing a “we” or “us” of followers. In a 2015 Hollywood Reporter interview, Miranda describes the power of art, pitting it against the work of politics: “Art engenders empathy in a way that politics doesn’t, and in a way that nothing else really does. Art creates change in people’s hearts. But it happens slowly.”45 Miranda frames the ethical obligation of art in terms of emotion and identification as an alternative to political activism. He reiterates this goal on Twitter in response to the comment of a follower about a playlist, saying, “It is literally my job…to make you feel things.” Miranda explains that he has “tons of practice” in producing art in order to cultivate specific feelings in the spectator.46

Figure 24. Screenshot of Miranda’s bio profile, January 2018.

His strategies for fostering intimacy with his Twitter followers finds its origins in the online marketing of his first musical. Elizabeth Titrington Craft’s research on Miranda’s use of YouTube for the promotion of In the Heights suggests that this social medium provided the means for Miranda to practice the discursive strategies that he currently uses on Twitter. In her essay “‘Is This What It Takes Just to Make It to Broadway?!’: Marketing In the Heights in the Twenty-First Century,” Craft analyzes the “twenty-three quasi-homemade videos posted by ‘Lin-Manuel’ on ‘usnavi’s channel’ on YouTube,” arguing that the “character-creator link between Miranda and Usnavi blurs the boundaries of ownership, suggesting these are personal contributions as well as products of the show.” The performance of this online persona, of Miranda producing videos as himself via the musical’s fictional character’s channel, is a precursor to how he deploys emotion and affect as @Lin_Manuel on Twitter in order to mobilize his audience. On YouTube, Miranda began “to fluidly cross boundaries between promotion and serious political commentary,” setting the stage for his full integration on Twitter. Key to synthesizing politics with the market is Miranda’s “enthusiasm for the internet and his ubiquitous presence [that] humanizes the show and its online promotional efforts.”47 Maintaining an active presence on YouTube, “regularly feeding new content to fans,” Miranda expanded the appeal of In the Heights beyond the traditional boundaries of Broadway. At the same time, producing new videos also translated into keeping the fans “continually engaged, bringing them into a community.”48

Miranda’s Twitter feed similarly cultivates a unique persona, one whose labor “for you” emulates that of an earnest, empathetic caregiver who cares about his individual followers and “everything” else.49 On this social medium, Miranda constructs an individualistic “I” as a self in the service of a community of intimates. Using the relational language of “for you,” Miranda produces original content for his followers as well as instructive messages about self-help enlightenment. The messages about advice and instruction comprise one-fourth of the intimacy rhetoric. Such advice is often predicated on Miranda functioning as a role model or representative agent for his followers. If we look more closely, analyzing only the corpus of “for you” tweets using Voyant, we find gratitude to be a rhetorical move that bolsters the intimate dynamics of Miranda’s Twitter account.

| Term | Count | Term | Count | Term | Count | Term | Count | Term | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hereís | 13 | gmorning | 6 | night | 5 | mix | 4 | heart | 4 |

| good | 12 | got | 6 | oh | 5 | need | 4 | i’ll | 4 |

| time | 11 | iím | 6 | order | 5 | protect | 4 | it’s | 4 |

| grateful | 9 | thanks | 6 | day | 4 | thank | 4 | life | 4 |

| playlist | 7 | know | 5 | gnight | 4 | make | 4 |

Figure 27. List of the top twenty-five words within Miranda’s 'for you' corpus.

By adding “you”-derived terminology to the stoplist (for example, “yours,” “you’re,” “yourself”) as well as references to emojis (flag, heart, hand), the Voyant wordcloud for the top twenty-five words reveals more clearly the centrality of Miranda’s performance of gratitude for his audience. This performance entails expressing gratitude for the support of Twitter followers, predominantly for a universal “you” rather than specific mentions of individuals.

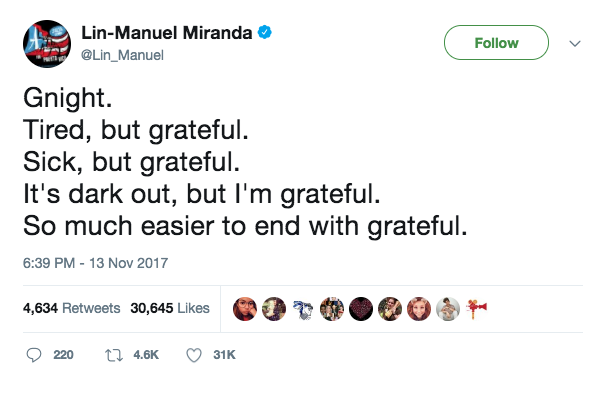

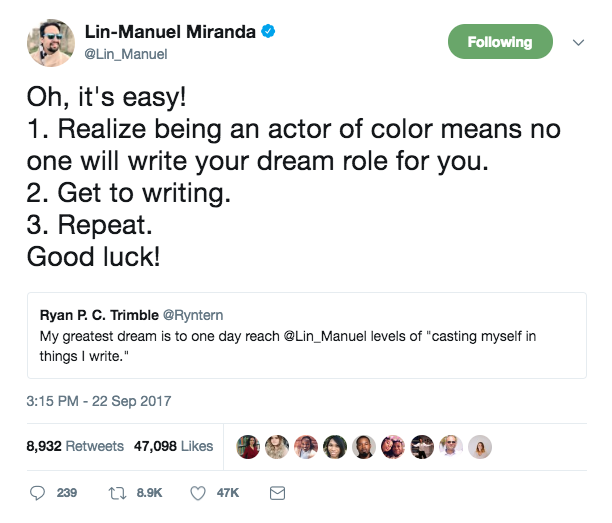

In data scraping Miranda’s Twitter account, I find that his rhetorical strategies on Twitter cultivate a caretaker/coach persona with a pedagogical investment in gratitude. When a follower, Ryan P. C. Trimble, comments on their desire to “reach @Lin_Manuel levels” of self-fulfilling creativity—“casting myself in things I write”—Miranda generates a post for all his Twitter followers that outlines an “easy” course of action: to acknowledge that there is a dearth of roles for actors of color, to start writing your dream role yourself, and to repeat this process of recognition and creative production.50

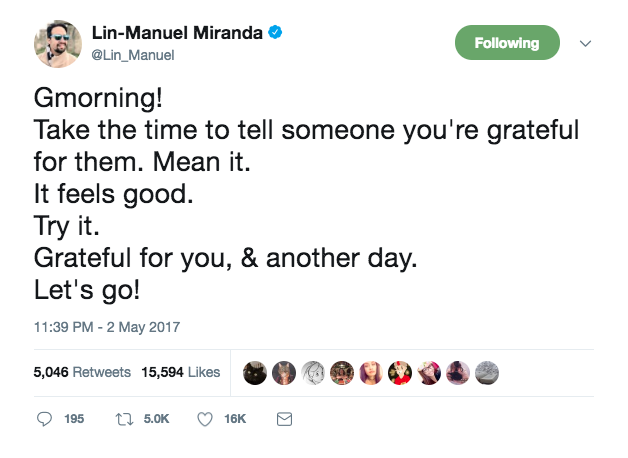

Miranda’s tweets often adopt this instructional tone, with a step-by-step outline, as in, for example, a May 2017 tweet that directs his followers, “Tell someone you’re grateful for them.” Miranda instructs on the benefits of maintaining such an ethos of gratitude, encouraging his audience to “mean it,” and pairs this directive with the promise that “it feels good.” Miranda then models that very process, saying that he himself is “grateful” for his audience.51 The promise of feeling part of a greater emotional good is fundamental to the intimate relationship Miranda seeks to build with his Twitter followers. The advice tweets are thereby bolstered by claims on the universal follower’s affect, through an implicit reciprocity.

Miranda’s performance on Twitter makes evident his investment in the audience’s ability to repay in kind, to yield positive emotion in response to his belief in the intrinsic good of his followers. Miranda advocates a kind of carpe diem philosophy in his tweets, often through the routine of greeting and expressing gratitude for his followers in the morning and evening. The success of this routine is manifested in the publication of his tweets in book form by Random House, which describes them as “pep talks.” This routine is a key facet of how Miranda builds affective alliances with his audience and can bank on their emotional investment when he needs to mobilize his followers.

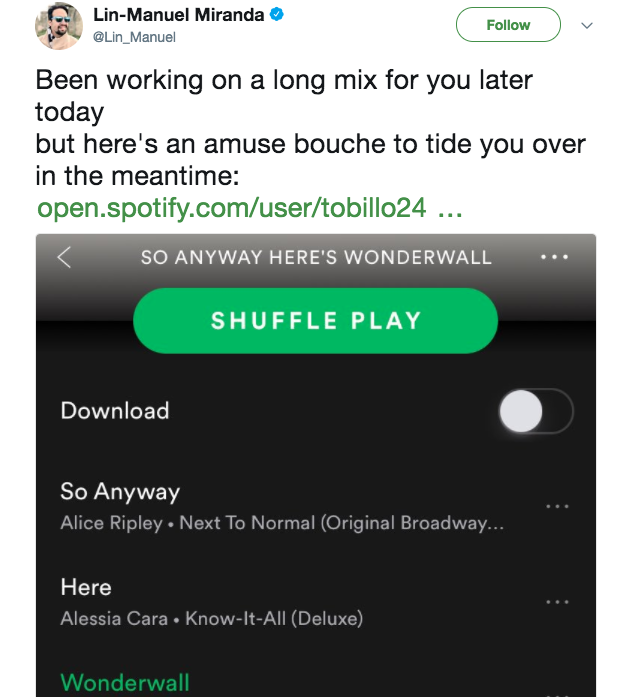

Miranda reinforces this grateful caretaker persona by generating music playlists for his followers, which comprise a third of the “for you” messages. These mixes musically imbibe the particular emotion or theme Miranda chooses to emphasize on a given day. Twitter serves as a vehicle for Miranda not simply to make things for his followers but to maintain a vibrant emotional connection with them. An exchange takes place when Miranda shares a music mix that translates a specific mood. He embodies an ethics of empathy, acknowledging the emotional needs of a universal follower and offering a music mix that can satisfy those needs. The labor involved in the production of original content becomes particularly evident in the queries from followers about when Miranda will share his next compilation of music. These requests reveal that Miranda’s audience comes to rely on the routine of sharing music, that this form of cultural production generates important ties between the playwright and members of his social media audience. Nonetheless, such requests also hint at the impossibility of sustaining such a project—is a follower ever going to feel satisfied with the rate of mixtape production? The challenge of cultivating intimacy online is that it requires an excess, at a nearly inhuman rate, of curation and cultural production. The greeting routine of expressing appreciation for followers or at least acknowledging their presence and investment in maintaining contact is one way that Miranda attempts to stay relevant on a daily basis with his millions of followers.

The “for you” invocation is also a vehicle for self-promotion, marketing Miranda’s various artistic projects, from the journey of the musical Hamilton beyond the Broadway stage to Miranda’s Disney films. While the fewest tweets are dedicated to these projects, at least in relation to the whole corpus of tweets, they do require mobilization of Miranda’s followers. In other words, the affective affiliation that is cultivated by the production of instructive messages, expressions of gratitude, and mixtape curation facilitates the financial success of Miranda’s other creative projects. The promotional appeals likewise share an emotional valence. In a May 2017 tweet, Miranda works in advance promotion of his voice-over character Gizmoduck in Disney’s reboot of the show Duck Tales. Rather than introduce the name or date of when the show would air (neither of which are mentioned), Miranda instead frames the image of his character with an expression of gratitude for his followers and the expectation that they will see it when it airs that summer. The tweet then builds on a sense of indebtedness, which begins with Miranda’s gratitude but ends with the gesture expected in reply—the audience’s consumption of his cultural production.52

Miranda’s tweet about the 2016 Disney film Moana follows an identical invocation as that of Duck Tales but elevates the cultural product or fictional character to the status of a human subject. The tweet frames the sneak peak of the film in terms of Miranda’s desire to introduce his followers to Moana: “I can’t wait.”53 Such terminology reverberates with the power dynamic of his followers requesting his mixtapes, invoking the same emotions of eagerness, anticipation, and hope. Expressions of affect translate into claims on future financial investment. Whereas the followers were the ones making requests, here it is Miranda who now places expectations on his audience to provide the emotional and financial support of his creative projects.

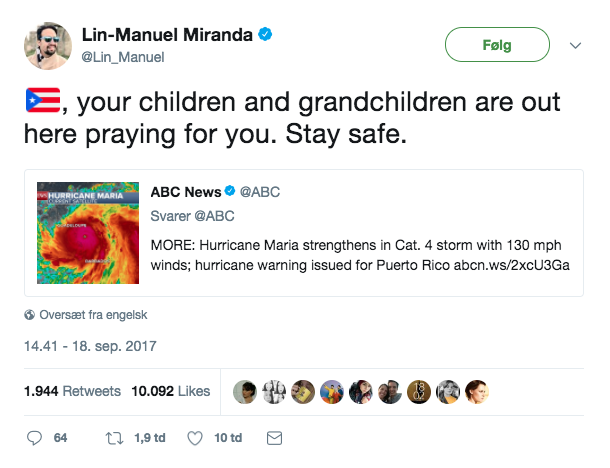

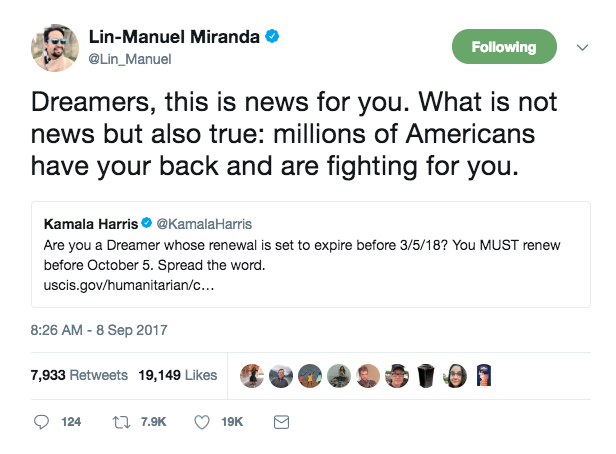

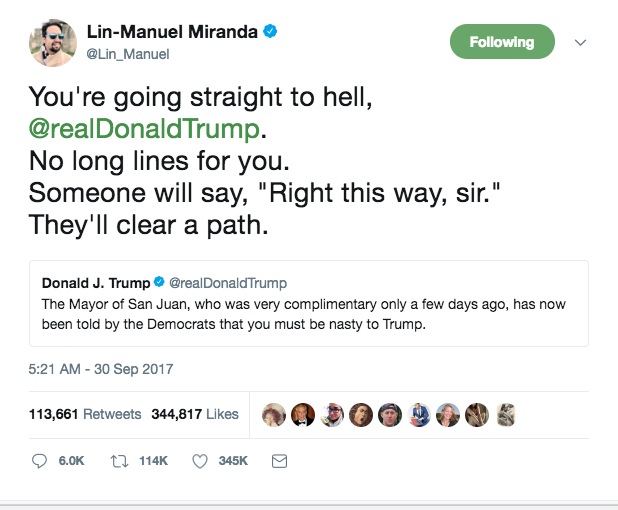

In terms of Miranda’s tweets relating to political activism, the “you” changes from referencing universal followers to specific personas, such as President Trump or the Dreamers. The dominant emotive valence of the messages tends toward that of empathy, with the exception of Trump. For example, Miranda posted expressions of sympathy regarding the August 2017 mass shooting tragedy in San Antonio, Texas, and Hurricane Maria’s disastrous landfall in Dominica and Puerto Rico in September 2017.54

Noticeably, these references to a specific population that has suffered trauma are paired with a change in Miranda’s self-referential language. Rather than retain a first-person voice, Miranda uses a plural form, a concerned and empathetic “we” in the cases of Texas and a community based on an ancestral lineage with Hurricane Maria. The rhetorical invocation of a shared community in struggle is also evident in the September 2017 tweet about the “dreamers.”55 The message passes along important information that was first posted by Senator Kamala Harris about the status renewal deadline for young immigrants in the United States. At the same time, Miranda’s contribution adds and affirms the existence of a supportive national community. Such moments of public commentary function as a form of activism that primarily focuses on rhetorically instantiating community. Miranda here reverts to a third-person narrative while implying that he acts as a member of a community that is “fighting” for immigrant rights.

The messages to Donald Trump take on an unusual tone in terms of the dominant emotional valence Miranda usually adopts in his tweets. Here, Miranda deploys the phrase “for you” to articulate a critique of the president’s failure to adequately support the hurricane recovery efforts in Puerto Rico. Both messages also rely on a third-person narrative, such that the “you” as personal address to Trump is not part of an intimate relationship of exchange. Additionally, the theme of waiting returns from the promotional tweets, but the expectation is quite different. Americans are depicted as awaiting the ethical behavior of the president, and when that behavior is found lacking, Miranda asserts that it is Trump who will not have to wait for his cosmic comeuppance.56

Miranda’s near silence regarding the 1 May 2018 protests in Puerto Rico against austerity measures is suggestive of the neoliberal limits to basing an articulation of philanthropy or ethics on affective affiliation. Thousands of protestors in San Juan took to the streets on International Workers’ Day, and the demonstration was predominantly peaceful until later in the day when the police used physical force and tear gas. The protest was covered by major news outlets, such as NPR and the New York Times; however, Miranda dedicated only a single tweet to the event. Miranda’s response relies on emotive language, emphasizing his individual reaction as “heartbroken” and “frustrated.”57 He does not contextualize the protest by referring to what it was about, the “cause” for which the protesters were rallying support.58 Miranda instead stresses his disappointment with the imagery and narratives that emerged. Without illustrating what he found troubling, followers are left to choose whether they will research the media coverage. Miranda’s tweet underscores his support of peaceful protests but does not articulate a shared ideological vision with protestors. Indeed, the third-person language of the tweet, referencing “the people of Puerto Rico” and “their treatment,” distances Miranda from the island’s population rather than his claiming them as community. There is no “we” imagined in Miranda’s response to this contentious political struggle over economic restructuring after Hurricane Maria.

Miranda appears to generally distance himself from Puerto Rican protest movements about the governance and economy of Puerto Rico, for example, he also made no comment on similar protests in 2017 (although he was also offline then, on a Twitter vacation). Perhaps it is too risky to invest the intimate ties that Miranda has established with his Twitter followers in public demonstrations that potentially include contentious clashes between police and protesters. At the same time, an aesthetics that is so dependent on a feel-good dynamic of gratitude to support the exchange of financial capital cannot dwell for too long on activism that challenges the logic of a debt economy.

Expanding Our Archival Vision

The limited temporality of Twitter’s window into contemporary discourse presents specific challenges to researchers who aim to identify trends by taking a long(er) view of the conversations. There are limited avenues available to retroactively pull an archive of tweets. The free programs available (Twitter Archiver and TAGS) only start collecting tweets after you first run them. In “Twitter’s and @douenislands’ Ambiguous Paths,” Jeannine Murray-Román notes of tweets, “They are inaccessible to the lay user once they have been displaced by new tweets. Otherwise, commercial social media monitoring tools…exist specifically to allow companies to store and dredge information from users’ tweets that are no longer viewable by the general public.”59 The expense of these commercial tools can be prohibitive for most scholars.

In addition, Twitter as a corporation sets legal limits on data collection. In “Studying and Preserving the Global Networks of Twitter Literature,” Christian Howard explains that “while anyone may theoretically collect Twitter data, Twitter’s Developer Agreement and Policy outlines strict limitations about how this data may be shared and stored.”60 Indeed, to access Twitter APIs (application programming interfaces), scholars need to apply to Twitter for permission to perform research.61 Applying for a developer account does not guarantee approval, and the circumstances under which an application is denied are not transparent. I can attest to this because my application was rejected, and there is no mechanism available to appeal such a decision. Twitter’s seemingly automated rejection e-mail ironically evokes Miranda’s aesthetics by attempting to offset the presumed disappointment of receiving a rejection with repeated gestures of gratitude: “Your Twitter developer account application was not approved. Thank you for your interest in developer access. We are unable to serve your use case at this time. Thank you for your interest in building on Twitter.”62

The social media and Web archiving project Documenting the Now offers a crowdsourced alternative to such corporate gatekeeping.63 As Howard notes in her essay, researchers “circumvent” the limits set by Twitter by sharing tweet IDs, since “up to 1,500,000 of which may be shared per user per month.”64 Howard provides a helpful overview of the process:

Tweet IDs are unique identifying numbers associated with each tweet that encodes the Tweet’s metadata. The metadata can then be obtained by running the Tweet IDs through a program or script such as the tweet ‘hydrator’ tool developed by Documenting the Now.65

Even this workaround has its limitations: “Tweet IDs from deleted tweets are unable to be hydrated, so unless someone else has captured and stored the data from those accounts, the deleted data is gone.” The other obstacle is that Twitter places a temporal limit on such archives, “specif[ying] that no entity may store and analyze Tweets ‘for a period exceeding 30 days.”66 While Twitter makes some exceptions to this storage rule, allowing for academic researchers to collect and retain tweets for longer periods of time, again, researchers’ status must be “verified” by Twitter, and the terms of that authorization are nebulous at best.

The problem posed by these restrictions and the limited alternatives available for archiving tweets and their metadata is compounded by the fact that the Library of Congress has stopped archiving the entirety of Twitter and on 1 January 2018 began “acquir[ing] tweets…on a very selective basis.” The Library of Congress possesses an archive spanning 2006 to 2017; however, it remains inaccessible or “embargoed” for an indeterminate amount of time.67 The disconnect with which I opened this essay remains: between the private world of social media and the public space of the library, between the tweet and the book as objects of literary analysis.

Even if Twitter made their collection of tweets open-access or the Library of Congress had the ability and means to document it all, why would academics want to engage an archive so compromised by the dynamics of surveillance and profit extraction? As a popular culture icon, Miranda’s mainstream popularity will surely translate into continued academic attention, with critics researching, historicizing, and analyzing his creative production and career on stage, in film, and online. The question remains whether the same critical interest will be dedicated to other Latinx cultural producers and their use of social media and to what extent such research will ethically engage those producers. Twitter will one day surely go the way of MySpace and other defunct social networking sites; what will be lost is more than a decade of discursive networks developed by minor US Latinx literary voices with varied and potentially contradictory articulations. Despite my ambivalence about the form and content of Twitter, I believe the study of US Latinx literature and culture will be at a loss if it does not draw its attention toward ethically analyzing the work of US Latinx writers on social media before those interfaces disappear and are replaced by new sites of public discourse.

The absence of a publicly accessible archive moving forward presents serious challenges to US Latinx studies scholars: How will the Twitter production of Latinx cultural producers be collected and preserved? Which tweets by Latinx creative writers will be acquired by the Library of Congress? Archival work within Latinx literary studies thus far concentrates on recuperating and circulating pre-1960s literature, most notably through the groundbreaking work of Arte Público Press and the Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Heritage project at the University of Houston. In 2017, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded the university a grant to develop the first US digital humanities center for Latina/o studies, which could indicate future academic investment in collecting and protecting the social media activity of US Latinx creative writers. However, the scope of this project currently remains limited to recovering a pre-1960s past, with the fellowship funds focused on supporting “several digital humanities projects involving work by Latinas and Latinos from the American colonial period through 1960.”68

Without governmental or academic sites for archiving tweets, there is no alternative contextualization possible for their production. While shifting tweets from the Twitter platform to these alternative spaces for research would not necessarily resolve the ethical quandaries of analyzing cultural production produced within a surveillance capitalist structure, such an archival process would hopefully create some healthy distance between researcher and corporation. At the same time, future archivists and researchers of Twitter production must continually reflect on how their work differs (or does not) from that of the surveillance capitalists, who do not just “host content but aggressively, secretly, unilaterally extract value from that content.”69 Perhaps secret is the key word that can distinguish our academic approach to social media labor and creativity. We must not only be transparent about our methodology but also explicit about our ethical failures. I can only hope that here I have begun to map out a form and process that gestures toward this intellectual transparency.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the expertise of Emily Sherwood, who served as the assistant director of digital pedagogy and scholarship at Bucknell University in 2017 and trained me to use TAGS, Twitter Archiver, and Voyant. I am also grateful to Diane Jakacki, Todd Suomela, and Christian Howard, who provided support for this project at its later stages. I want to thank my colleagues who provided invaluable feedback on various drafts: Jeannine Murray-Román, Bill Orchard, Inmaculada Lara-Bonilla, Marci R. McMahon, Dennis Sloan, Lilianne Lugo-Herrera, and Marcos Steuernagel. A final thank you to all the scholars who engaged my presentations on this research at the Latina/o Studies Association, Latin American Studies Association, American Comparative Literature Association, CUNY Colloquium for the Study of Latina/o/x Culture and Theory, Modern Language Association, and American Society for Theater Research conferences.

-

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Gmorning, Gnight! Little Pep Talks for Me and You, illus. Jonny Sun (New York: Random House, 2018). ↩︎

-

Lin-Manuel Miranda (@Lin_Manuel), “Gmorning! A bit of news—At YOUR request, we made a book of the Gmornings & Gnights! Illustrations by @jonnysun! Available October 23! We love you!,” Twitter, 17 July 2018, 5:00 am, https://web.archive.org/web/20180717122340/https://twitter.com/lin_manuel/status/1019190030387073025. ↩︎

-

I draw on my prior work situating Miranda within a broader history of US Latinx politics as well as the institution of Broadway theater in particular; see Elena Machado Sáez, “Bodega Sold Dreams: Middle-Class Panic and the Crossover Aesthetics of In the Heights,” in Dialectical Imaginaries: Materialist Approaches to US Latino/a Literature in the Age of Neoliberalism, ed. Marcial Gonzalez and Carlos Gallego (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), and “Blackout on Broadway: Affiliation and Audience in In the Heights and Hamilton,” Studies in Musical Theater 12, no. 2 (2018): 181–97. In both essays, I make the case that Miranda’s In the Heights and Hamilton ambivalently balance a counter-narrative to a history of stereotype on the Broadway stage with the goal of convincing the predominantly white, highly educated tourists in attendance that the “other” is one of them. Having written these essays addressing the themes of belonging, race, politics, class, and audience, I am interested in investigating how the copious amounts of text that Miranda produces via Twitter conveys a broader philosophy on the intersection of aesthetics and politics on social media. ↩︎

-

Patricia Ybarra, “How to Read a Latinx Play in the Twenty-First Century: Learning from Quiara Hudes,” Theatre Topics 27, no. 1 (2017): 49. ↩︎

-

Twitter homepage, 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20180717110859/https://twitter.com/. ↩︎

-

Christopher B. Balme, The Theatrical Public Sphere (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 4–5. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 7. ↩︎

-

Dorothy Kim, “The Rules of Twitter,” Hybrid Pedagogy, 4 December 2014, https://hybridpedagogy.org/rules-twitter/. ↩︎

-

Dorothy Kim and Eunsong Kim, “The #TwitterEthics Manifesto,” Model View Culture, 7 April 2014, https://modelviewculture.com/pieces/the-twitterethics-manifesto. ↩︎

-

Elizabeth Losh, Hashtag (New York: Bloombury Academic, 2019), 110. ↩︎

-

Sydette Harry, “Everyone Watches, Nobody Sees: How Black Women Disrupt Surveillance Theory,” Model View Culture, 6 October 2014, http://modelviewculture.com/pieces/everyone-watches-nobody-sees-how-black-women-disrupt-surveillance-theory. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Lisa Nakamura, “The Unwanted Labour of Social Media: Women of Colour Call Out Culture As Venture Community Management,” New Formations, no. 86 (2015): 106. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 108. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 110. ↩︎

-

Macarena Gómez-Barris, introduction to Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 13. ↩︎

-

Dorothy Kim, “Social Media and Academic Surveillance: The Ethics of Digital Bodies,” Model View Culture, 7 October 2014, http://modelviewculture.com/pieces/social-media-and-academic-surveillance-the-ethics-of-digital-bodies. ↩︎

-

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019), 111–12. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 112. ↩︎

-

Elena Machado Sáez, “Permission Request to Cite Tweets in Academic Publication,” e-mail message to Marissa Chibas, 19 September 2019. ↩︎

-

Helena Webb, Marina Jirotka, Bernd Carsten Stahl, William Housley, Adam Edwards, Matthew Williams, Rob Procter, Omer Rana, and Pete Burnap, “The Ethical Challenges of Publishing Twitter Data for Research Dissemination,” in WebSci’17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Web Science Conference (New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018), 340, 342. 341. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 343. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 341. ↩︎

-

Marissa Chibas Preston, “Re: Marissa Chibas ‘Permission Request to Cite Tweets in Academic Publication,’” e-mail message to Elena Machado Sáez, 27 September 2019; Charlie Vázquez, “Re: Permission Request to Cite Tweets in Academic Publication,” e-mail message to Elena Machado Sáez, 20 September 2019. ↩︎

-